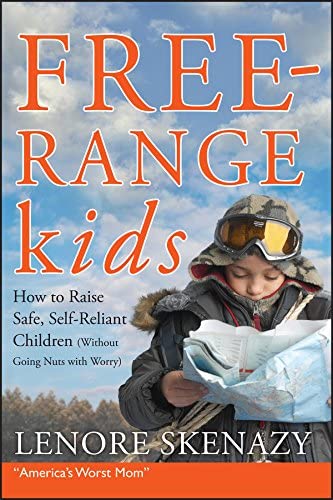

At his request, Lenore Skenazy let her then-9-year-old son ride the train home by himself—and was subsequently labeled as the worst mother in America. Since then, Lenore has founded Free-Range Kids, a movement designed to let children be, well, children, and give them the freedom and independence that they need and deserve. We spoke to Lenore about free-range parenting, hosting her TV show, World’s Worst Mom, and why helicopter parents get a bad rap.

Lenore, let’s talk about the incident that started it all.

When my younger son was 9, he asked my husband and I if we could take him someplace he had never been before in NYC and if he could find his own way home on the subway. We talked about it, and my husband showed him the subway map so we knew he knew how to read it. And one Sunday, I took him to Bloomingdales and told him that today was the day. I didn’t just abandon him! [laughs] So I went one way, and he went into the subway and he talked to a stranger and asked if this was the right direction, and the stranger told him where to go. He took the subway a couple of stops and got off on 34th Street, took the bus home, and when he came into the apartment he was…levitating? He had done something grownup that he felt he was ready for and we believed in him. I think that’s been the entire tenor of this movement.

What was the response?

I wrote an article like a month and a half later because it wasn’t an experiment; it wasn’t a publicity stunt. It was real life: “Why I Let My 9-Year-Old Ride the Subway Alone,” and two days later, I was on the Today Show, MSNBC, Fox News, NPR—defending myself for having let my son do this. I started my blog, Free-Range Kids, that weekend, because I needed to have my voice. I love my sons, and I wasn’t doing this because I was publicity-hungry, or that I didn’t care if he never came home or not. We did it because he felt he was ready, and we had to decide that yes, he was ready. My blog said, “I believe in safety, I believe car seats and seat belts and mouth guards, and fire extinguishers!” I just don’t think that kids need a security detail to leave the house. And that’s different from a lot of the prevailing notions.

Now, had your son not asked to go on the subway or get home by himself, would you have suggested it to him?

No. We have an older son who didn’t ask and he hadn’t taken the subway by himself at 11. It was a question of that the kid came up with the idea and then evaluating it. What occurred to me about four years later that in almost every interview, there comes a moment when the interviewer leans over, and if she can, touches my knee, and says, “But Lenore, what if he never came home?”

Oh, I wasn’t going to ask you that.

[laughs] Because you’re not them! You’re great, and I appreciate that. But the fact that it came up so often and I never knew what to say, and I realized that I didn’t have an answer because it wasn’t a question. How would I feel? I think you would know how I’d feel. I’d feel outrageously devastated, regretful, and remorseful. The thing I had done wrong, my crime, was that I didn’t think that way before I let him go. And to be a good parent today, you always have to go to that very darkest spot, imagining yourself wallowing in regret, explaining yourself to Anderson Cooper, fighting off the people on Facebook—if you’re not going to that place, you’re not caring enough.I think that there’s just so much fear, but the majority of it is unsubstantiated. You hear one bad story and you think, “That’s going to happen to me!” unless I go to that dark place like you said.

You do go to that dark place. I call it “worst first thinking.” You have to come up with the worst case scenario first, and then proceed as if it’s likely to happen. And when you have a whole culture doing that, that’s why I don’t blame the helicopter parents. Because if you’re in a society where you can get a knock on the door because your kid is walking home from the park or from school alone, you have a society that’s insisting that you’re wrong unless you’re concerned every single second that it could be your child’s last and therefore you must be there to save them. It’s a hysterical moment; it’s not just worry. It’s a society that’s making us crazy. Society is telling us, “Your children are in constant danger.” Everything they see, do, meet, eat, every single play date, sleepover, toy, it could hurt them-

It’s not like your child could fall, or fail, or break a bone, which is all normal kid stuff. It’s more like, “Your child will die, and you will suffer horrible guilt for the rest of your life.”

Right, and then we make parents feel more guilty because it’s like, “Why are you stunting them?” Poor parents cannot get a break. But in addition to being completely fearful for our children’s health and well being and safety, but it also seems if we’re not a constant presence, either physically or electronically, they will forget that we love them. There are so many articles, like “How to write the perfect note for your kid’s lunch.” I think the connection with my kids is strong enough that it will last from 9:00-3:00.

When I give lectures, I ask the audience to think of something they loved doing as a kid, but that they don’t let their own kids do. They talk in little groups, but sometimes the thing people remember turns out to be a bad memory. One time I was doing an interview with Jesse Ventura, and he told me that one time he was riding my bike when he was 10-years-old. He had ridden his bike two miles, and fell off and he completely mangled his leg. And there were no cell phones, no one with him, and there was no way to get home except to get back on the bike with the mangled leg. Which meant with one foot he had to push the pedal down, and then he had to wait for it to come back up so he could push it back down again because he couldn’t use the other leg. He got home and it turned out he had broken his foot. But here it is, 50 years later, and he’s done all these things with his life, and he’s telling me this story, with a kind of joy and pride. Why? Because he’s the boy who broke his foot and nonetheless got himself home with nobody else’s help. But we keep trying to take these opportunities out of our children’s lives and we assume that any unpredictable event will be the end.

As parents, we need to give our child those moments.

Apart from giving them self-confidence, I think there’s something deeper. When you’re constantly with your children, yes, they know that you love them, but they also get a sense that you don’t believe in them.

Something else that I do during my lectures is to ask people to think of someone who wasn’t nice to them, and then to think of someone who believed in them, even before they believed in themselves. And sometimes, they open their eyes, and they’re crying. It’s a teacher, grandma, or an aunt. That’s who we want to be for our kids. And if we’re doing everything for our kids, they get the message that we love them—and that we don’t believe in them. So why would we want to do that to our kids, when we’re so grateful for those people who believed in us? I feel like that’s what’s been taken out from us, this belief in our kids, your community, and your own parenting.

How do you think the kids of today will be as parents in the future? Do you think they’ll be free-range or will they adopt some of their parents’ parenting styles?

I’m bad at predicting the future. But because there are so many cheap and easy ways to monitor everything in our lives, I do worry that an unmonitored childhood will become the exception and my dystopian fear is that it will become illegal.

Let’s talk a bit about your show, World’s Worst Mom.

I got a call from London one day asking if I was America’s worst mom, and I was like, “Yeah.” [laughs] It was a television production company asking if I wanted to do a show based on my book. We did 13 episodes of World’s Worst Mom—they bumped me up from America’s Worst Mom to World’s Worst Mom—on Discovery Life. [laughs] It was international, and it had an interesting premise. It was me going to the homes of 13 extraordinarily nervous, anxious families where, for example, the mom still fed the 10-year-old in his mouth. Or a mom who got her 8-year-old a skateboard, but he could only stand on it on the grass. My job was to meet with the parents and hear all their fears, and then separately meet with the kids, and ask what are you not allowed to do. I would write down what they couldn’t do, and then we would pick things for them to do.

But in doing the show, I saw that something amazing happens when parents get to see their children growing up. When a parent gets to see their child do something, like ride a bike, run an errand, walk to school, they did something a little grown up, the parents’ pride is so overwhelming. And it changes parents instantaneously. At the end of the show, I would show them the list of the things their kids couldn’t do, and they would look at the list like they couldn’t remember why they couldn’t do any of those things.

That’s why I started doing The Free Range Kids project in schools. The teachers ask the students to go home and write down one thing they feel that they’re ready to do, but for one reason or another, they haven’t done yet. And when the kids do that, because their parents have signed on to do it, it’s a one-shot deal, and the school is telling them to do it, or maybe the kid gets extra credit, they do it, and the parents cannot believe how fantastic their kid is, and how smart, and look how they’re growing up!

And the fear goes away.

And the fear goes away. So the fear that’s brought to us by the media, and the marketplace, and social media, or something scary that someone said, poof! You should get your school to do the Free Range Kids project, it’s on my site, and it’s free.

But my new push is legislative. Some parents are afraid that if they let their kids walk home from school alone, they’ll be arrested. Parents shouldn’t have to worry that if they think their child is ready to do something that the cops or Child Protective Services will come knocking on their door and arrest them. What I’m trying to do is get towns to declare themselves Free Range Towns. What I’m trying to do is get them to pass the Free Range Kids Bill of Rights. It’s one sentence long: “Our children have the right to some unsupervised time, and we have the right to give it to them without getting arrested.”

Once a town declares itself free range like that, it means that even if you don’t feel that your child is ready to walk by himself to school at 12, but I feel that my child is ready at age 8, I get to do that without worrying that the cops will come get me. And if they see my kid and he looks confused, I’d still like for them to do their job and make sure he’s okay. So you still have all the pieces in place of child protection, but you’re raising your kid in a town where you know that they want him to be outside. They like the parks being filled with children playing; they like seeing kids coming and going to school. And if I had a choice of living in a free-range town that encourages this kind of community and happiness that we had as kids, versus the next town over that the parents would like to send their kids outside but they’re afraid that they’re going to get thrown in jail, I would choose Town A. I think at some point this will catch on and towns will adopt a Free Range Kids Bill of Rights. It doesn’t mean that we don’t care about our kids; we care about them very much. We are supporting the parents who are letting them grow up and eventually be part of the world. I think in ten years’ time, it will be normal to be a free-range kids town, with happy children playing outside.