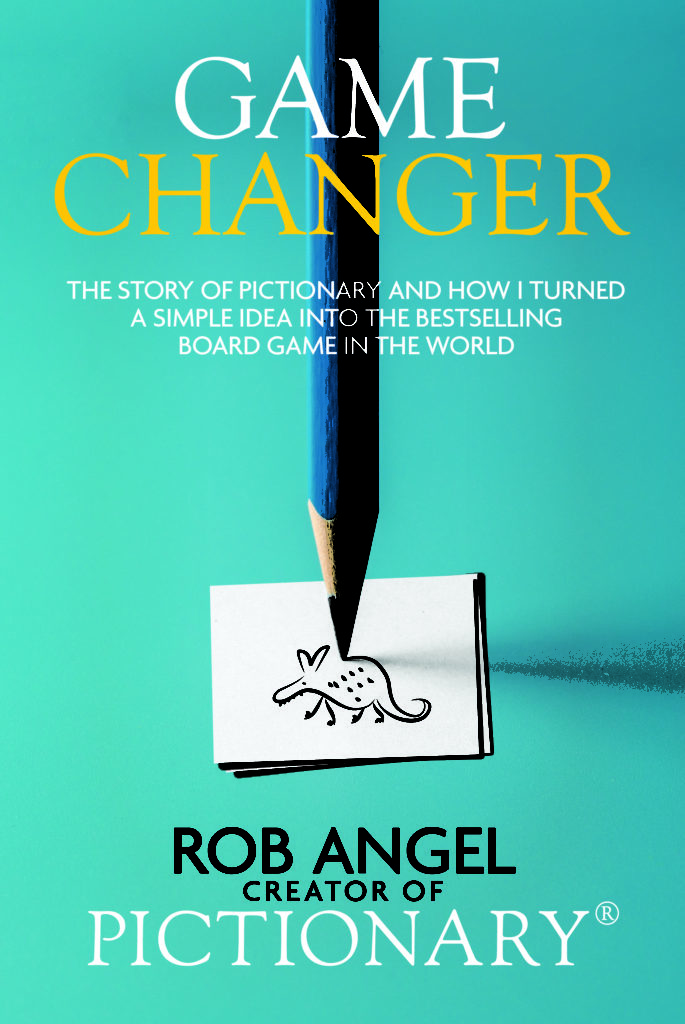

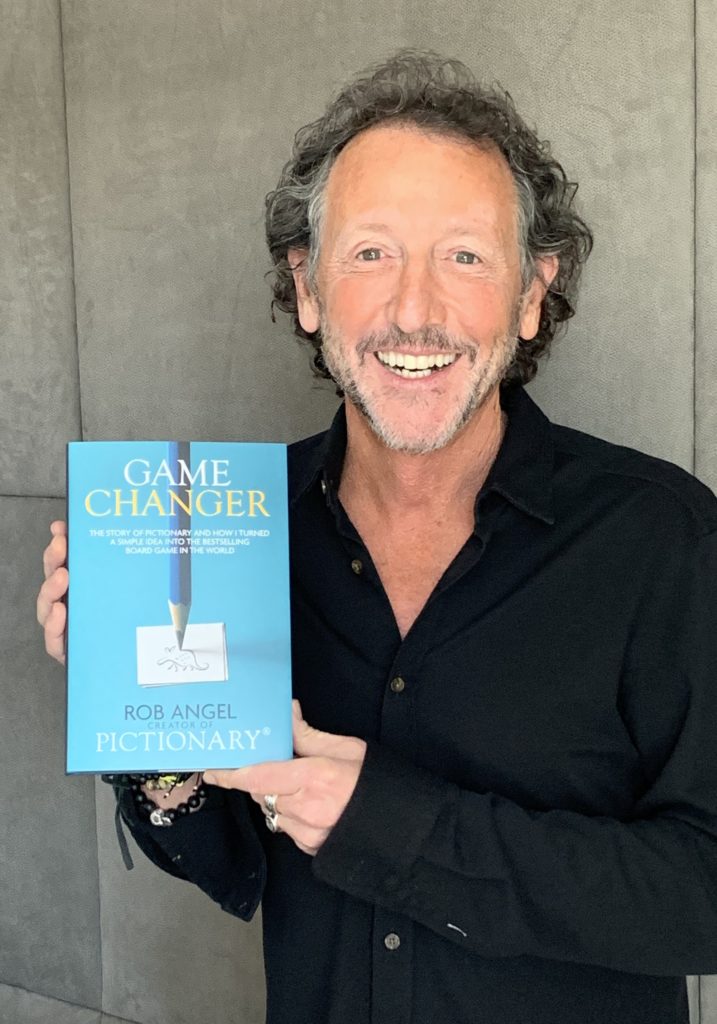

Board games have seen a resurgence of sorts lately, particularly during the pandemic. That might explain why it’s almost impossible to get a copy of Pictionary, the board game that tests your artistic skills—and your sense of humor. Since it debuted in 1985, Pictionary has gone on to become the bestselling board game of all time. And now, Rob Angel, the creator of Pictionary, has released his book, Game Changer: The Story of Pictionary and How I Turned A Simple Idea into the Bestselling Board Game in the World. We spoke exclusively to Rob about Pictionary, how it’s okay to not have a plan, and how a guy who can’t draw well went on to create the biggest board game of all time.

Pictionary is celebrating its 35th anniversary. What does that mean to you?

It’s bizarre to think that it was 35 years ago on June 1st. It was always my intention to create a great game and everything else would come from that. The stories that people tell me are mind blowing and humbling to me.

I think there’s a surge more towards tech-free activities. And with the quarantine, I find this to be even more so.

I’m hijacking a term: high tech high touch. The more we get into tech, the more it becomes normal. The more high tech we get, the more touch we want. We want to touch things, that tactile connection, and that’s the beauty of Pictionary. Because really, the beauty is in its simplicity. You can open the box and within in two minutes, you can be playing. You know how to draw and you know how to guess, and that’s all you need.

Let’s talk about your new book, Game Changer.

It was time to write it. It took about five years. It is a great story and I’m so pleased with it, talking about how and why I started Pictionary in my apartment up to now.

What do you want people to get from your book?

It’s okay not to have a plan when you start—just start. We tend to overthink things, myself included. When I first came up with the concept for Pictionary, I thought, “I’m going to do this; I’m going to create something.” But then all this negative self-talk took over. “Oh, but I’m just a waiter.” But then all the steps necessary to get Pictionary on the shelf took over as well. I could see it; that was my vision. But marketing plans and business plans came into play and I just shut down.

So I thought, “What’s the smartest, simplest first step I can take?” And it was the word list, because everything I had was right there. I had a piece of paper, a pen, and a dictionary. I went into the backyard and I literally wrote down the first word that made sense, and it was “aardvark.” I wrote it down on a yellow legal tablet, and literally my life changed in that moment. I still didn’t have this idea, this plan, but I just got started. I was no longer a waiter. My mindset changed, and I thought, “I’m a game creator.” And then it was a matter of taking the next step, and the next step, and it was just a one foot in front of the other process. After about 14-15 months, I was able to look up, look past my nose, so to speak, and look for the big plan.

Even if you have an idea, it can be very tough to start.

They tell you to write down the steps, and then take them one at a time, but that didn’t even work for me. Had I written down all the steps, I would have kept looking forward and not gotten started. And with this book, I’m doing it all again. I’m figuring out what my next step is. I want people to read it; it’s a good story. It’s just the unknown.

What can parents glean from your book?

Being a parent of a 24 and 26 year-old, I remember these days very well. For the kids, let them be creative as they want to be, and as they can, and give them as much visual stimulation as you can. When creativity comes from opening your mind to new things, if they are watching something, you never know what’s going to come in from there. And maybe it will show up on something they draw. I teach kids to not be afraid of the unknown. They should explore new ways to come into their psyche, subconsciously or not, and that, for me, really helps to create a process.

For sure, drawing is a great form of meditation and the ability to be in the moment.

Absolutely. One of the great hallmarks of Pictionary is this great collaboration and being in a group. When you’re playing, you’re never alone. You’ve got a teammate. And the worse you’re drawing, the more you’re in on the joke. People are laughing at you, and you’re laughing at them. It’s a beautiful dynamic that everyone is in on the joke. So it just liberates you to just keep drawing. You’re drawing and your mind is going and all your senses are going at the same time—it’s like going to a concert. People remember Pictionary stories from 20 years ago, not because of their specific drawing, but the emotion that they felt when they drew it and who was around them. And when you’re playing Pictionary, you get to be a kid again.

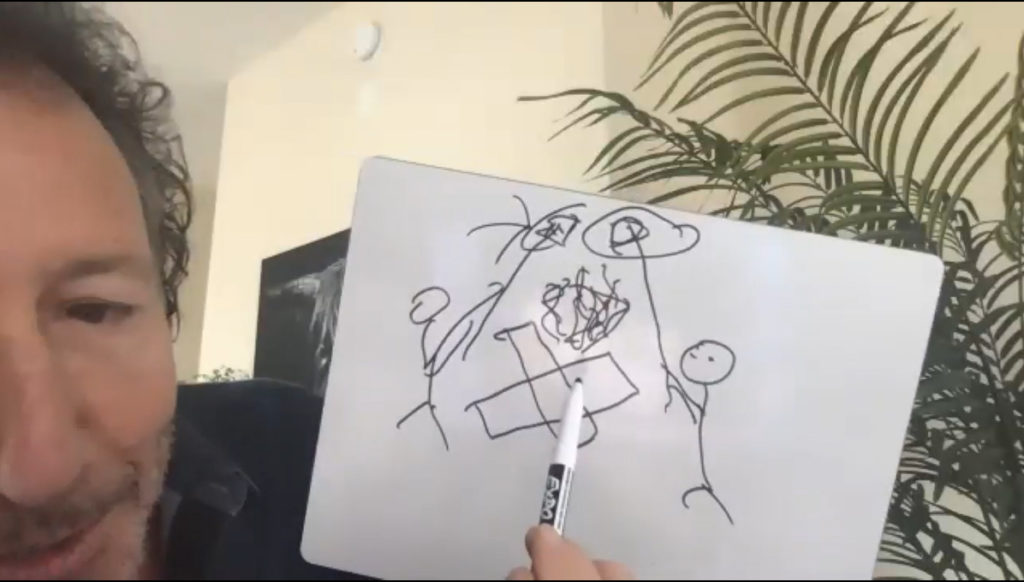

When we were scheduling the interview and I knew that we were going to play together, I thought, “Wait, why am I doing this? I can’t draw.”

[laughs] I would not get too confused about that. I will pull out my pad and pen and show you—Mr. Pictionary can’t draw. If you want me on your team, it’s not an advantage.Do you ever think about making another game?

Pictionary is my baby. I’ll be linked to it, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually forever. I did another game called ThinkBlot after Pictionary based on the Rorschach Test, but I think there’s another game in me.

I’m doing more speaking, telling my story, because it’s important to me. With kids, they’re all confused. They want to know what their future looks like. I want to share my story and let them know that it’s okay not to know. I graduated from college but I didn’t have a plan, but I knew I was going to do my own thing. That was my mindset. I kept my eyes open and that’s when Pictionary came along. I call it ambiguity, there’s a lot of fun in ambiguity and not knowing. People get afraid of it, but guess what? The unknown is going to happen. It’s all unknown. I talk about changing your mindset from being afraid of the unknown to making it a part of who you are.

When your kids were younger, how often were you playing Pictionary with them?

When they were very young, we played quite a bit, and I generally lost. But when I played with them as adults, almost always, I was on the losing team.

That’s hilarious.

It’s interesting, because one of the main reasons I wrote the book was to chronicle what Daddy did. My kids knew bits and pieces, and they see the game and know that I created it, but they don’t know the struggles that I went through. The deep down purpose was for them to get a sense of it, and the best part of writing this book was near the end, when I talked to my daughter about it. She was 25, and I would talk to her about it, and she said, “Why don’t you send me a chapter?” I was kind of nervous because it’s out of context. So I sent it to her, and she sent it back with some changes that she recommended. She helped edit the book, and now this whole new dynamic with her has come about. Not only is she reading the story, but she’s living it with me, too. It’s given us this whole new understanding and appreciation of each other. It’s taken our relationship to a whole new level. It’s been such a blessing.